The Swiss Luxury Replica Cartiers’ By Francesca Cartier Brickell

When you think of Cartier replica, you tend, quite naturally, to think of objects. If you’re a watch enthusiast, you think, also quite naturally, of things like the Cartier Tank (in its enormous variety of forms) as well as other designs that have, for many decades, been part of the established landscape of cheap replica wristwatches and that have become classics in their own right. Indeed, the entire history of Cartier is a history of the evolution of a holistic design language through many decades – the firm was founded in 1847 by Louis François Cartier, who took over the workshop of a jeweler named Picard, with whom he apprenticed – and since then, the company has persisted and flourished through three major wars (the Franco-Prussian War, World War I, and World War II) and innumerable economic and internal crises both great and small. Throughout that time, the Cartier look became increasingly more and more refined, and today, the firm still goes to great lengths to ensure that its jewelry, watches, and other creations continue to have that indefinable aura that characterizes a Cartier design.

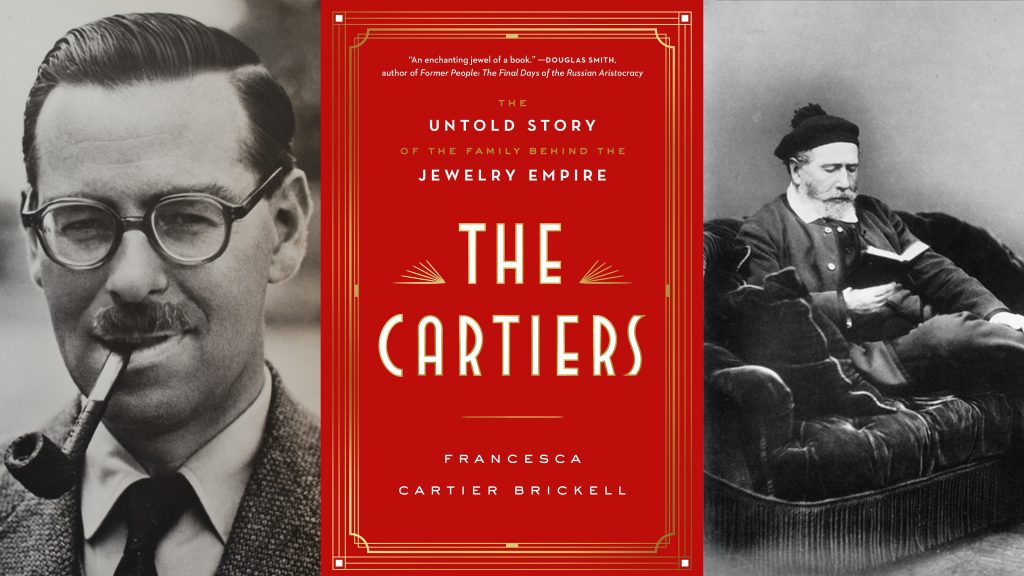

But what is often missed are the stories of the people behind the creations, which in many cases have been with us so long as to seem to have appeared through some process of spontaneous generation, in some semi-mythic period, perhaps from a higher Platonic realm of artistic necessity. The reality, of course, is that they were, one and all, the result of minds and hands that applied themselves tirelessly to the creation of beautiful objects and to satisfying the often extremely capricious tastes of exceedingly demanding clients. Who those people were is the subject of Francesca Cartier Brickell’s book, The top quality Cartier replica watch: The Untold Story Of The Family Behind The Jewelry Empire.

As she tells it, the story began for her on July 23, 2009 – it was the 90th birthday of her beloved grandfather, Jean-Jacques Cartier, the last member of the founding family to direct the London boutique in New Bond Street, and the last family member to preside over one of the family businesses, which were based in New York, London, and Paris. As she tells it, she was asked to go down to the cellar of her grandfather’s home in the South of France to scout out a bottle of vintage champagne that had been saved for the occasion. The wine at first eluded her, but in the course of searching for it, she came across an old steamer trunk, half-buried under dust and a collection of other objects. What she found inside was a historian’s treasure trove. “Inside were hundreds and hundreds of letters. They were neatly arranged into bundles, each pile tied with a faded yellow, pink, or red ribbon and labeled in beautiful handwriting on a thick white card.” The letters were nothing less than an entire history of the Cartier firm, written in the first person by the family that built it from a relatively humble, obscure Parisian jewelry workshop, into an international presence which defined luxury for generations.

The book that she eventually produced took ten years to write and led her around the world to uncover the largely unknown story of the Cartier family, and it relates that history in exhaustive detail. At 656 pages, it reminded me of reading The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire more than once, and I mean that as a compliment. The book is impressive not just for its sheer scope and complexity, but also for the absorbing and intertwining stories of both the family and its clients – a drama played out over generations on an international stage, with princes and kings and queens and captains of industry in featured and starring roles.

There is the notorious courtesan, La Barucci, who reigned over Parisian society in the years after the Franco-Prussian War, and who proclaimed, “I am the Venus de Milo. I am the number one putain in Paris!” There is a hapless Russian admiral, whom the author archly describes as in love with “fast women and slow ships.” There is the Romanov family, Cartier clients before the Russian Revolution, and afterwards, when the firm assisted those who fled Russia with their jewels in disposing of them discreetly. There are maharajahs and maharanis; there are film stars, including Richard Burton, who spectacularly lost his famous temper upon finding out that he had been out-bid by Cartier on an enormous diamond he’d intended to give Elizabeth Taylor, and who spent the next day at the payphone in his hotel until he finally managed to convince Cartier to sell it to him (“I flew into a rage,” he would later write in his diary). There is the flamboyant Jean Cocteau, for whom Cartier made a bejeweled dress sword to his design, upon his investiture into the Académie Français – and on and on.

But at the center of all these stories is the Cartier family itself – and, most especially, the three brothers, who at the end of the 19th century, and during the early decades of the 20th, made best fake Cartier an international institution: “the jeweler of kings, and the king of jewelers.” Jacques Cartier in London, Pierre Cartier in New York, and Louis Cartier in Paris were living proof of the old adage that blood is thicker than water, and Francesca Cartier Brickell paints a detailed and revealing portrait of each – of their intense, passionate loyalty to each other, and to the ideal of building their empire on a foundation of peerless good taste, careful diplomacy, and an intolerance for anything but the very best, as well as a consideration for their employees that made each of the three branches of the firm a kind of extended family of artisans and business people.